From the pen of the first woman editor-in-chief of the Philippines, a tribune of Philippine journalism from the time of the dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, till today, here is the book's foreword, which is often an indication of what the rest of a book may just yield for the reader... Click here, too, for a recent review of the book by the writer Robert JA Basilio, Jr. Both courtesy of the Department of Shameless Plugging, of course...

From the pen of the first woman editor-in-chief of the Philippines, a tribune of Philippine journalism from the time of the dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, till today, here is the book's foreword, which is often an indication of what the rest of a book may just yield for the reader... Click here, too, for a recent review of the book by the writer Robert JA Basilio, Jr. Both courtesy of the Department of Shameless Plugging, of course...FOREWORD TO

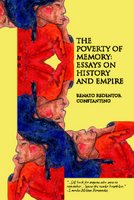

THE POVERTY OF MEMORY:

ESSAYS ON HISTORY AND EMPIRE

Lourdes Molina-Fernandez

(CFNS, QC: 2006)

ISBN 971-8741-25-9

Of all the things that one could be bankrupt of, none could be as tragic as an inability to remember. And to learn enough to understand the lessons of what deserves repeating and what must forever be avoided.

A moral bankruptcy, if one believes enough in a forgiving supreme being, might be remedied, for all its seeming irreversibility, by some miracle working in a man’s heart. Needless to say, all other kinds of financial bankruptcy may be reversed. But to empty a memory bank is the worst condition of all. So why, one asks, does this thing keep happening every day in every corner of the planet? Why do follies big and small keep recurring in some form or another, like some economic cycle, despite the abundant and increasingly sophisticated means for monitoring and documenting everything that happens in our lives? One answer: there are means for such tracking and telling -- technology that's pervasive, swift and creative -- but the controls are held mostly by those with a greater interest in keeping certain truths out of people's reach. The gods of truth, they who man the gates where mostly "damned lies and statistics" may pass if useful to their interests, have such an all-pervading ability to influence minds everywhere that there's only so much anyone with a bare passion for honest story-telling can do to get across the details and the message.

To be sure, the levers are held not only within the world of mass media: for the controls in mass media, telecommunications and information technology, interlocking all, are linked firmly and continually to the controls in all the other industries and interests that rule the world. The merchants of oil, the merchants of war, the merchants of lies -- insulated by the brilliant merchants of law who can so easily dictate the terms and limits by which the planet is to be used and by whom, and how much risk people will be exposed to, wittingly or unwittingly.

When I agreed to write the foreword for this book, I thought it would be a good companion primarily for journalists—considering the painstaking effort that its author has put into each piece, in order to weave together history, the breaking story, and the lessons as distilled by social scientists and witnesses both, in one seamless tapestry.

I was wrong. This is a book for anyone who cares to remember, whether the chronicles are written as journalism, or as timeless literature; whether the stories happened this century or the last, or even four centuries before; or whether the persons in them, though set apart by creed or greed, by color of skin or of views, or by class or interest, have something to teach.

Those unfamiliar with the author's style may be uncomfortable initially with how he likes to juxtapose context and people. He jumps from past to past-past to present to future and then back, citing events and people and places with such ease and speed he leaves the reader breathless. In Red's writings, heroism and cowardice are timeless. Nobility of heart knows no creed or color; it may spring in some black American soldier who refuses to kill Filipinos at the turn of the century, knowing they are defending a freedom they won from a foreign power, only to be snatched by a new colonizer. Or in a whistleblower who refuses, though he is "just a mechanic," to be a cog in a secret nuclear machine and thus pays for his refusal with 18 years of his life in prison.

This same ability to string together memories of long ago and of recent vintage, memories of empires lost and still ascending, and connect the dots each time, shows Red’s ability to make the difficult transition between chapters. He jumps, not just from one era to another, from one empire to the next, but also from one oppressed people's struggle to another: whether it's the Philippines after its hijacked revolution at the end of the 19th century, or Indonesia's pogrom after Suharto's ascent to power -- cheered on by the same powers that cheered on a Philippine dictator, only to dump them all when they outlived their usefulness; or East Timor suffering 24 years of annexation while much of the world kept quiet.

He reminds us, lest we forget, that much of today's macho rhetoric against "terrorism" and "terrorists" are actually just ways to cover up a long string of unscrupulous policy: how those who rejected conventions against biological and toxic weapons years ago now threaten to invade countries seen harboring them, and pressure allies into passing sweeping anti-terrorism laws, on pain of economic sanction, with provisions that will not really stem the tide of terror.

The same thread of feigned concern and useless, two-faced solutions run through the new horrors of a new age: to climate-change and global warming issues where the culprits who shunned the Kyoto Protocol spout rhetoric about the need to stop the petroleum addiction and promise support for renewables, while justifying an illegal invasion in the world's biggest oil basin.

I have gone over more than 90 percent of the essays Red included in this book, because they appeared in TODAY newspaper, where I was editor for many years. Still, however, re-reading each one triggered some epiphany of sorts; a joy in seeing complicated stories of basic universal themes told so effortlessly and with just enough passion; but also, a burden in yet again being reminded of the tragedies of our times. Tragedy upon tragedy in an endless stream of diverse stories cannot, however, be anywhere as heartbreaking as the tragedy in not remembering -- the cry of the book from end to end.

Three important lessons I bring with me always since re-visiting the articles: first, while the rich and powerful control the levers that open the gates of truth, we just need enough people, as Red paraphrases John Pilger, to speak out, and urgently. Two, while the "narratives of the occupier" may often dominate the telling of the story, we just need enough people to write the alternative narrative from the ground -- constantly, wherever and whenever possible, as our own Mosquito Press did, not too long ago. Third, history never runs out of cruel lessons, and that cruelty must be matched by a certain ruthlessness in stripping the gods of lies of their "nobility of intention."

There are risks, as always. That is the lot of whistle-blowers, Cassandras, prophets, messengers of bad news, journalists, through time and across empires. This book tells their stories as well, and gives us hope that in whatever context, it is always better to pick the right and the good, because, as every story here keeps repeating, what goes around, comes around. #

BACK TO RED's MAIN PAGE

MORE OF RED's ESSAYS

LETTERS TO RED

No comments:

Post a Comment